EDIT ML

In the summer after my junior year of high school, I worked on the EDIT ML internship with Dartmouth College. The program gave me the opportunity to work with experts in the field of computational pathology on real cancer research that could potentially lead to faster and more accurate diagnoses for cancer patients. I worked on a team of three high school students total under Dr. Joshua Levy.

Our research focused on a small portion of a larger cancer diagnosis workflow. When pathologists study disease progression in patients, they often conduct biopsies to study tissue hidden beneath the skin. This tissue is subsequently imaged and studied to identify where the tumor is located and how severe it is. Because human analysis can sometimes be fallible, many attempts have been made to automate the tumor detection process using machine learning classifiers.

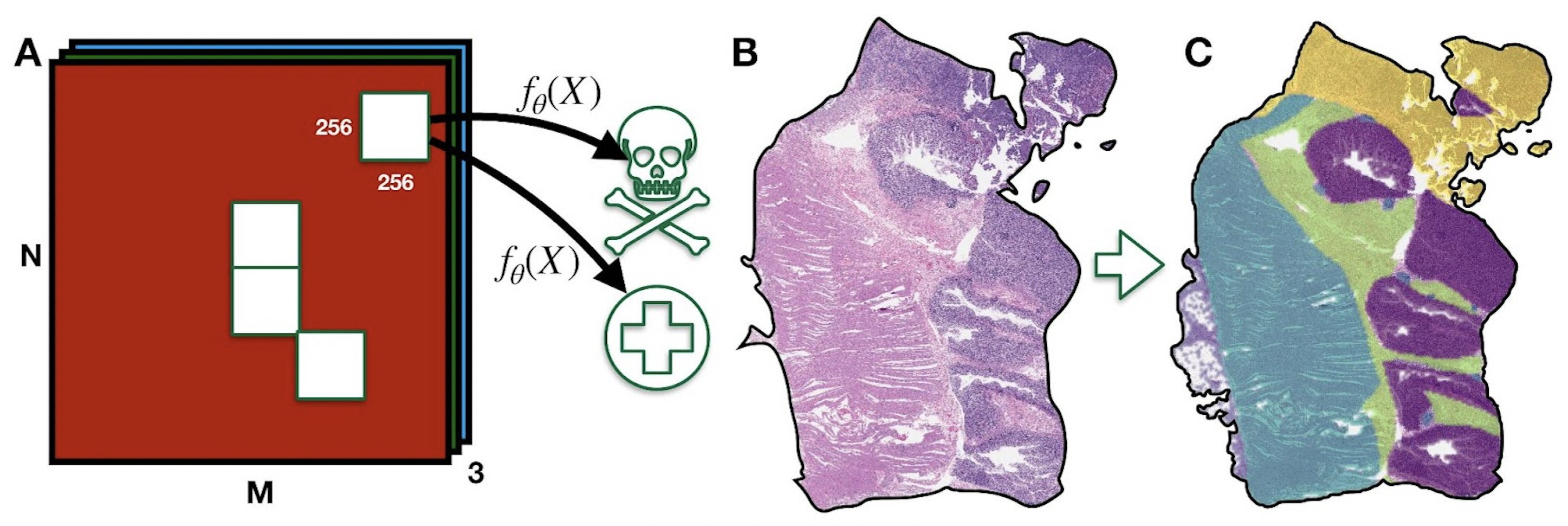

A whole-slide tissue image being broken into 256x256 units, each of which gets classified as benign or malignant.

A whole-slide tissue image being broken into 256x256 units, each of which gets classified as benign or malignant.

Creating a simple tumor vs. non-tumor classifier is easy and for the most part a solved problem. But one remaining issue that existing tumor classification models face is that the data they’re trained on often includes ink annotations created by pathologists to easily identify the tumor in an image when communicating with their patients or other pathologists.

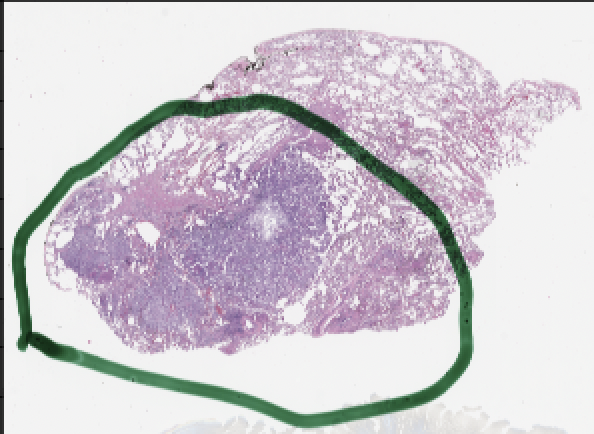

A whole-slide image that has been annotated with green ink to show the location of cancerous cells.

The obvious problem here is that models can learn to cheat using the ink annotations instead of actually learning to identify cancerous areas of a whole slide biopsy image. This means that when they face real-world data that hasn’t been annotated by pathologists, they perform far worse than they did on the training dataset. Our research attempted to solve this problem using domain adaptation: training a model on one dataset such that it can be applied to a different dataset.

Our approach to domain adaptation was to preprocess our source dataset to make it “look” like the target dataset before training a classifier. That is, we wanted to take images with ink annotations and turn them into images without ink annotations. Several methods exist to do this, but we tried something novel: Graph Neural Network (GNN) imputation.

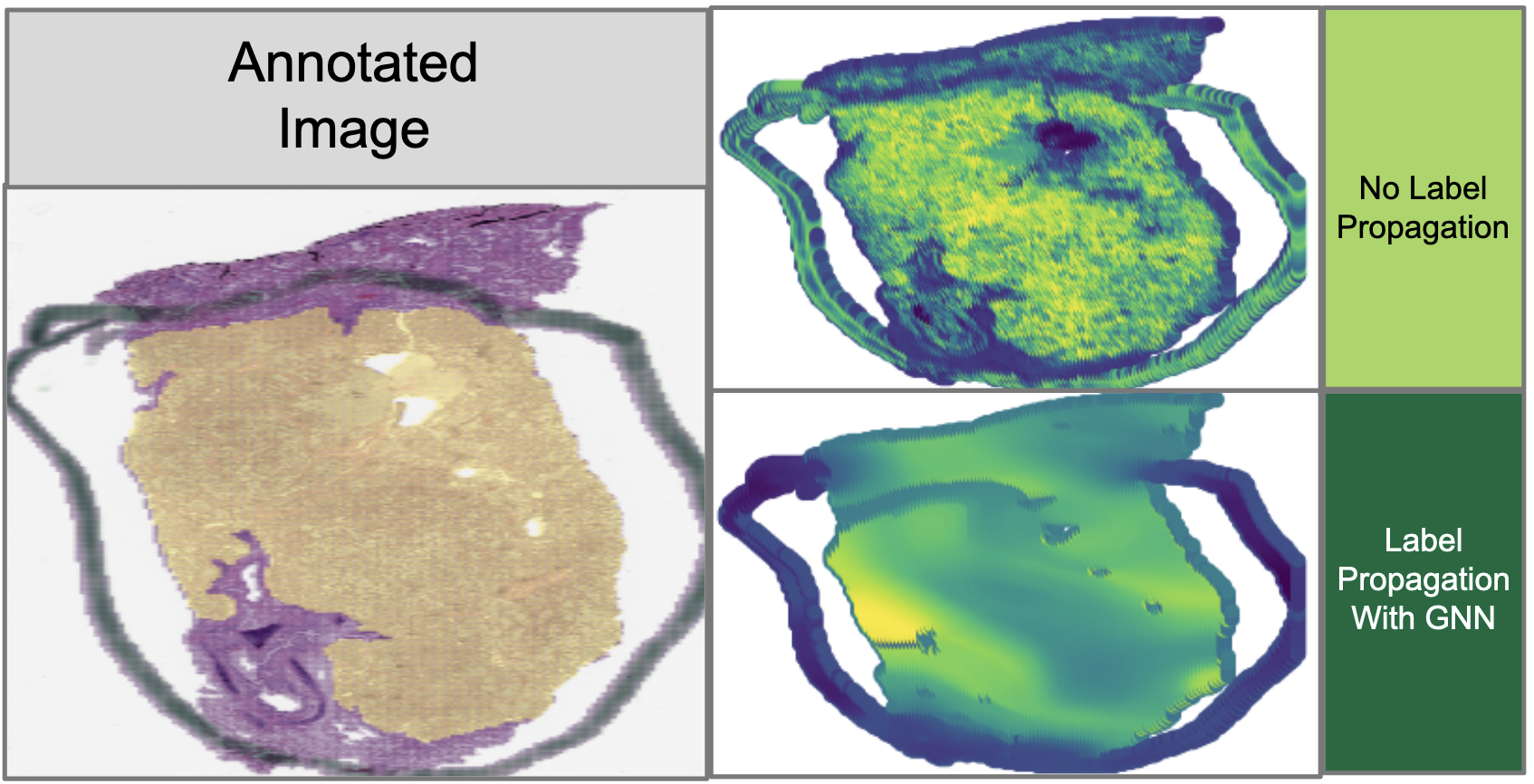

A comparison of tissue images both with and without our GNN information imputation. These are very preliminary results.

A comparison of tissue images both with and without our GNN information imputation. These are very preliminary results.

The idea here is to essentially first convert the image into a set of embeddings, and then “blur” those embeddings using a GNN to dilute the presence of ink annotations. By doing so, we could impute the information underneath opaque ink by using the information in surrounding patches of the image. To validate that this GNN method is indeed the best method of imputation, we compared it against a more traditional Cycle-GAN imputation method that uses a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to generate ink-less images from images with ink annotations, given example datasets of annotated and unannotated images.

As of the time of writing, this project is still in progress, and we’re still waiting to see what our final results are going to look like. But (fingers crossed) this might lead to a publication in the future. Because even though our part in the overall chain of cancer diagnosis and treatment is small, the fact remains that this work is going to help people once it’s complete, and that’s something worth working towards.