TJ Space Program

The name “Space Program” is actually something I created towards the end of my senior year; for most of my high school career, the club was called TJ NanoSat. This was because its primary mission was to build small cube satellites (known as CubeSats) and launch them to orbit. One of the club’s biggest accomplishments is the successful assembly and integration of its first independent satellite, TJ REVERB (many years prior to this, there had been a separate satellite built by a different team in partnership with Orbital Sciences—read more about that here).

ISS CubeSat launch video from Nanoracks, our launch provider.

Early Interest

REVERB had been started in 2016, long before my time at TJ, with the original mission of testing the Iridium satellite communications system from Low-Earth Orbit (LEO). I first heard of the project in my 7th grade, right as I was considering future applications to TJHSST, a local magnet school. I remember that looking at their website, I was completely transfixed by the potential to work on a real satellite that would actually be launched to space as early as high school. I mean, who wouldn’t be, right? It’s a REAL satellite! Going to REAL space!

Screenshot of the old website’s landing screen, the source of my desire to join the team.

Screenshot of the old website’s landing screen, the source of my desire to join the team.

In the hopes of one day joining this team and working on REVERB, I submitted an application to TJHSST in 8th grade and was graciously accepted. At the very first opportunity in my freshman year of high school, I submitted another application for the team, and was again graciously accepted. Thus began four years of work on one of the most unique and unforgettable projects I’ve ever undertaken.

2018-20: Ground Station

For my first two years on the team, I was assigned to work on our APRS ground station (so that we could communicate with the backup APRS radio on the satellite, if necessary). The primary accomplishment that I have to show for my work during this time is that I did manage to create a working, launch-ready ground station, as well as write software to allow someone on the ground to use it.

But what I really accomplished during this time is learning. I walked in with zero Python experience and zero familiarity with Linux, and by my second year I knew Python in-depth and considered Linux to be my second home. Not to mention, I learned how to solve problems on my own by doing my own research instead of relying on others to be my tech support.

My one regret from this time is not being more actively involved with REVERB itself. Because my work was mostly insulated from the satellite proper, I didn’t get the experience of working alongside more experienced members and learning what I could about satellite design. This gap in knowledge transfer would prove to cause me problems down the line.

2020-21: Balloon Project

At the beginning of my junior year, it became clear that virtual learning was here to stay, and that progress on REVERB was effectively stalled until the pandemic died down. So I decided to start a small sub-project in order to attract new members and keep interest going: TJ Balloon. The mission’s goal was to evaluate 5G signal strength at various altitudes above a cell tower.

While we never ended up launching our balloon, we did complete all aspects of the project up to assembly; the hardware is currently sitting in a cabinet in TJ’s robotics lab, and the software was complete and ready for testing. Plus, the project gave our club some much-needed new members, without whom REVERB’s eventual completion would’ve been impossible.

2021-22: Project Management and REVERB Completion

In the summer before senior year, I was told that I would be TJ REVERB’s project manager (our club’s topmost position at the time) for the coming year, and that it would be my responsibility to finally get our satellite off the ground. I was also told that because of our pandemic delays, NASA’s CSLI launch grant would expire in one year, meaning this would be our last chance to get the satellite launched. If we slipped for any reason at all here, there would be no second chances.

Not only that, but because I’d never been very involved with the satellite itself up until now, I had no idea what the true state of things was until I took inventory myself to find out. As of that summer, we had a fully-wired flat layout of our satellite’s components (which we called a FlatSat) that, according to the previous year’s seniors, supposedly worked. We had undocumented flight software that was confusing to the point of being more difficult to complete than just totally rewrite. We had a tiny team composed only of those few of us who hadn’t already jumped ship because of our difficult position. We had alumni who, for the most part, had moved on to their college experiences and were either unable or unwilling to offer us help. Outside our club, almost nobody even knew we existed because we hadn’t made a single social media post in years. And we had only one mentor left who’d stuck with us through everything.

Overcoming this challenge wasn’t something that anyone really believed we could do. I actually got laughed at quite a bit for putting so much time into a project that most people saw as a lost cause. But the impossible odds aside, this was my satellite that I’d believed in for the past three years, so I was determined to see it launch.

Software

My first order of business was to get things moving again with our hardware and electronics by getting someone to verify that the FlatSat was actually working as we’d been told. I also tasked someone with re-establishing our online presence so that people would once again know what we were doing. With the few programming people I had left, I shifted our focus to software, deciding to take on the challenge of a full rewrite. I ended up writing a good 60% of our final Python flight software (pFS) personally, with the rest filled in by the more junior programmers on our team.

Testing

By February of 2022, we had a fully-written flight software and a verified-working FlatSat, so we began doing software tests and group code reviews. This is when people really started to believe that our satellite would launch, so I also began pushing for recruiting new members so that we could keep the club after REVERB. I personally brought our team’s only woman onboard during this time in an effort to increase diversity and cater to a wider audience of potential members down the line. I also initiated work on a paper that we could submit to the national Small Satellite Conference in order to create opportunities for increasing our visibility and making connections with potential sponsors for our next mission.

Final Assembly

Final satellite assembly began in April 2022 and ran into early May. Past generations of students had given us CAD for the whole satellite and had machined out some custom components necessary for our design. However, these were created on a low-quality machine and proved to be unfit for a satellite. We had to re-mill all components on TJ’s in-house milling machines. Once our hardware was all ready, we followed instructions prepared by past CAD teams to assemble the satellite. During this time, I was finally able to take something of a back seat and let the most qualified of us handle assembly; our progress up to now was enough to convince even our most firm deniers that REVERB was going to launch, and our team worked with a spark of passion and inspiration.

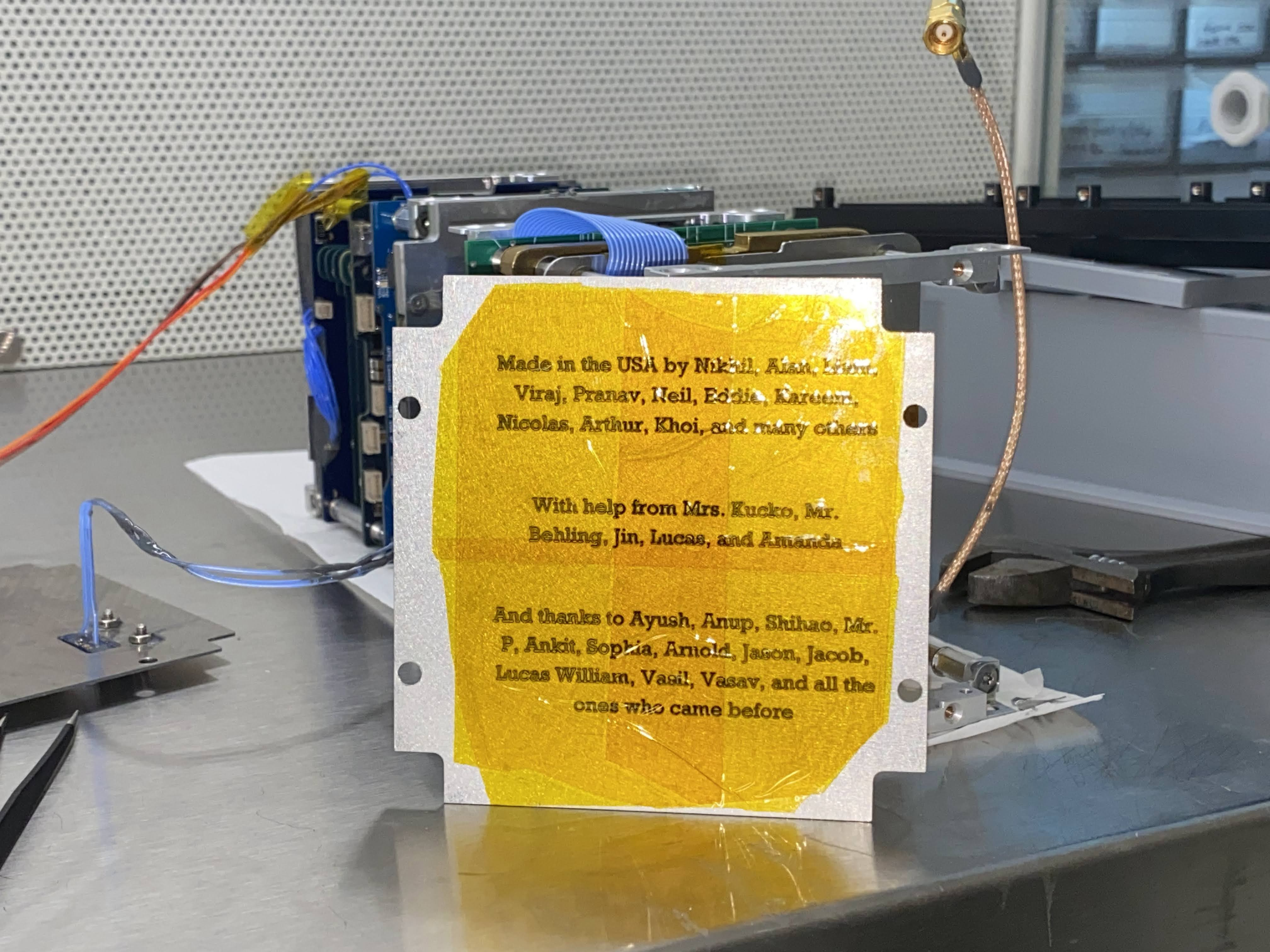

Laser engraving on REVERB’s bottom plate, resting on partially-completed satellite.

Laser engraving on REVERB’s bottom plate, resting on partially-completed satellite.

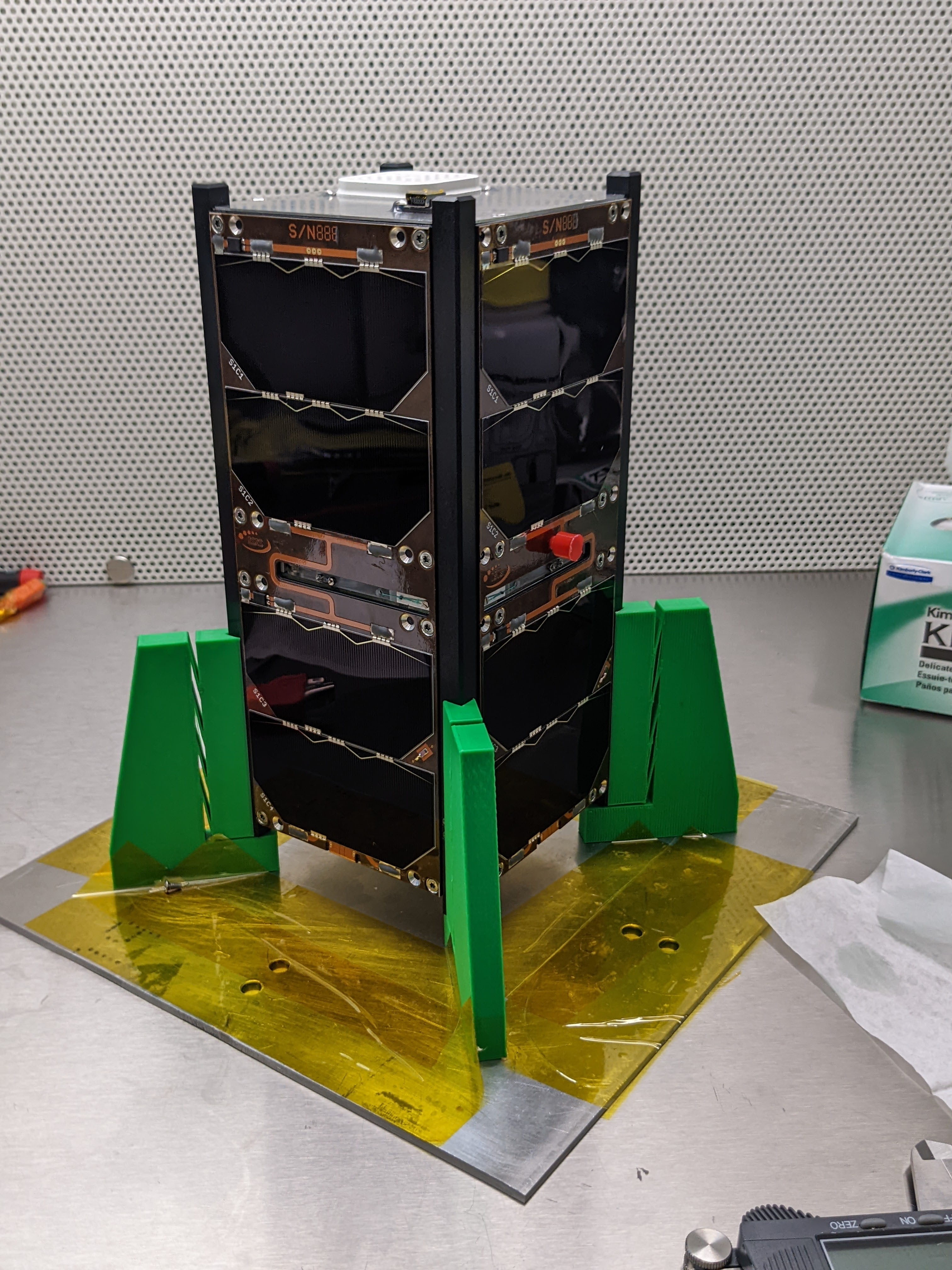

Completed satellite, resting on a 3D-printed holder.

Completed satellite, resting on a 3D-printed holder.

Post-Assembly

After REVERB was assembled, launch was almost guaranteed. However, there were still a few steps we had to take before it could be launched to orbit. During this time, I was mostly involved with administrative tasks in order to ensure that the club would continue long into the future. I initiated two new missions: an entry-level chip satellite that would get launched to the Moon’s surface, and the world’s first high school LEO research platform, with space available for others in TJ to conduct their own research in the vacuum of space. I also was heavily involved in recruiting new members, posting about our progress on social media, and writing two new papers aimed at sharing our experiences with REVERB with the world. Perhaps most notably, I spearheaded the club’s rebrand from TJ NanoSat to TJ Space Program so that we could tell the world in the boldest way possible, “We Are Back!”

Vibration Test

In late May, we visited the US Naval Academy in order to conduct a vibration test and verify that our satellite could survive the ride to the ISS on SpaceX’s Falcon 9. REVERB passed, and after the documents were submitted to Nanoracks (our launch provider), was cleared for integration and launch. While there, we also got to watch the Blue Angels perform a flyover for some honorable guests.

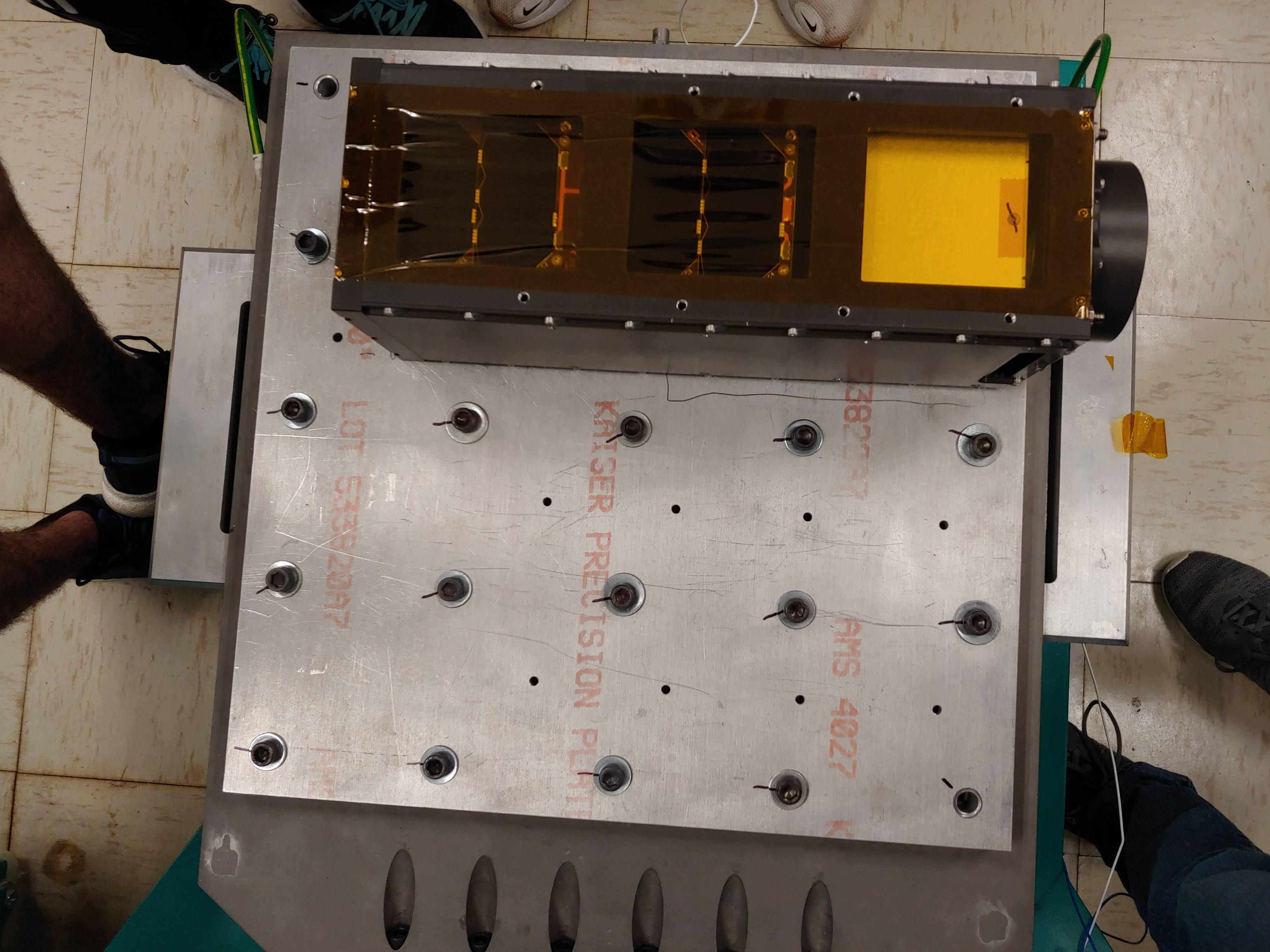

REVERB strapped in for its vibration test.

REVERB strapped in for its vibration test.

Blue Angels flyover at the US Naval Academy.

Blue Angels flyover at the US Naval Academy.

Integration at Nanoracks

In mid-July, some of our younger members flew to Houston, Texas, to integrate REVERB into its launch vehicle. This was a major step towards launch, representing the point where the satellite was finally “out of our hands.” I consider this to be the true “completion date” for REVERB.

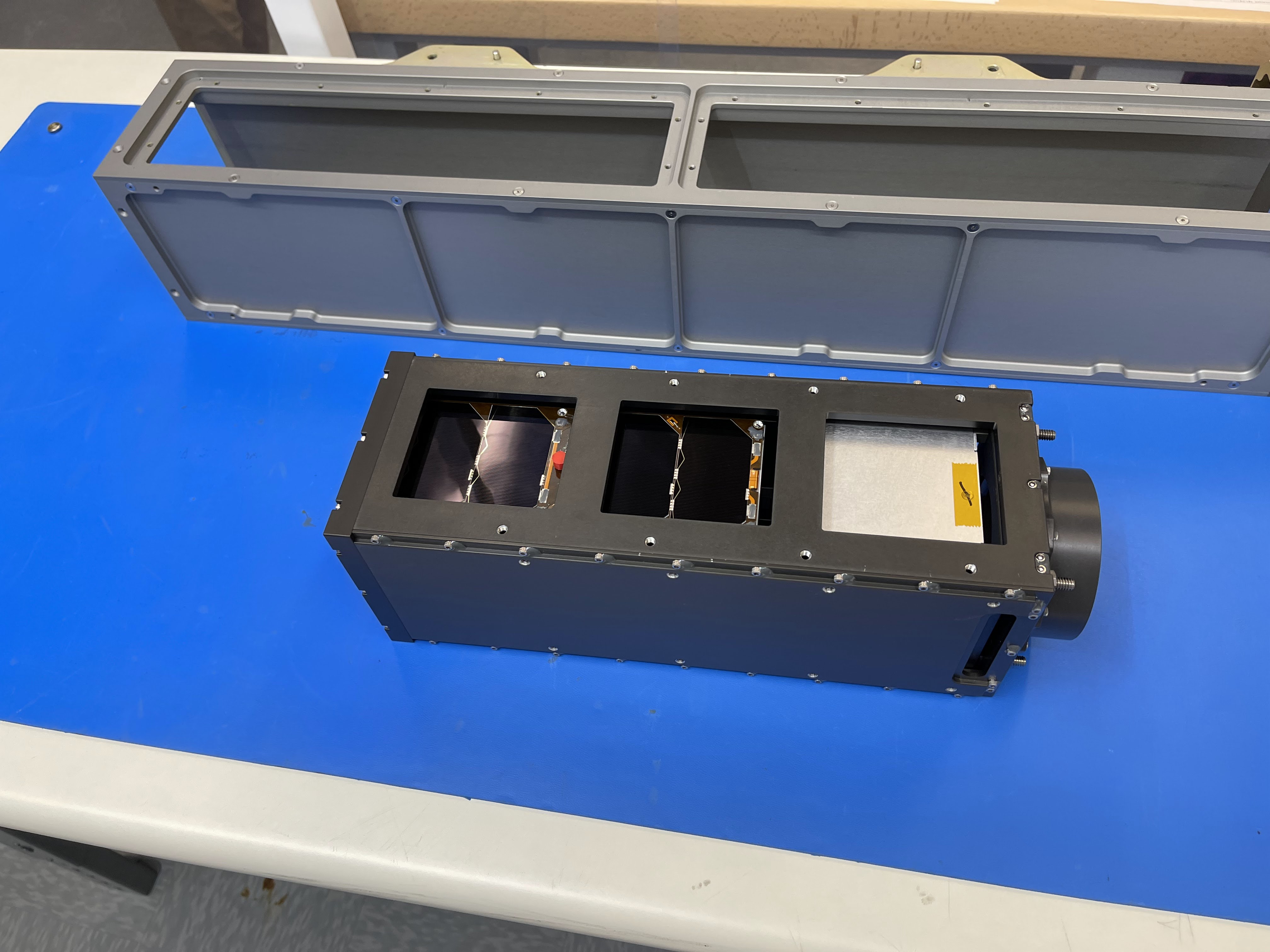

REVERB at Nanoracks’ integration facility

REVERB at Nanoracks’ integration facility

Publications

I was directly involved in writing two major publications: one studying the experiences of other high school CubeSat programs, and another sharing our own experiences and lessons learned with others in the small satellite community. The first was accepted and published at the Small Satellite Conference in Logan, Utah in the fall of 2022. Our entire team visited and presented our work for a full 15-minute timeslot alongside universities like MIT and Georgia Tech. We also manned a university-level booth and took advantage of the opportunity to secure funding, sponsorships, and support for future missions. Many other CubeSat teams in attendance, both at the high school and at the university levels, gave us accolades about how accurately our research captured their real experiences. See the full paper here.

My second publication was a recollection of our experiences building a CubeSat without a kit as a high school team, and an explanation of the problems we faced and our approaches to solving them. This was accepted and published in IEEE AeroConf’s 2023 conference proceedings. A huge amount of effort went into this from many members of our team and our results were quite interesting, so I strongly recommend reading through the full paper when possible. See the full paper here.

A third publication about the technical design and challenges we faced has been submitted to IEEE and is pending peer review.

Public Appearances

Here’s an interview I did during the conference where I and a few others on my team answered questions about our experiences. Here’s another with the TJ Partnership Fund, and here’s a feature we got from the school after launching. Also, NASA did a feature of the CSLI grant, and one of our photos ended up on the front page. Never before have I regretted being out of frame this much…

Launch

As of the time of writing, REVERB is still sitting in a Nanoracks facility, waiting to be launched into space this October. I’ll update this page once that happens (with pictures!).

What’s Next?

TJ Space Program has moved forward from TJREVERB to new missions, and hopefully will start more new missions as those get completed. For me and the others who graduated from the program, we all intend to be as much of a resource for future generations as we can so that knowledge and skills can keep accumulating. My time at REVERB taught me how to lead people and build a community, and I hope to use those skills in the future wherever I end up going.