Vex Robotics

Middle School

I competed in the Vex Robotics Competition (VRC) in all three of my middle school years. VRC played a pivotal role in developing my love for STEM, and served as the foundation for most of the work I’d later do in high school. This is where I learned the principles of programming, engineering, and strategic thinking. My school curriculum barely touched on any of these ideas; I had to learn everything on my own through trial and error and lots of Googling.

The central idea for all competitions is to construct a robot that fits within multiple design constraints (size, motor count, official Vex parts only, etc.) that performs best in a 2v2 game. You have one alliance partner to work with and two opponents working against you. What the goal actually is depends on the game specifics for that year of competition. This way, the challenge is fresh every single year, and the “perfect robot” changes regularly.

Competitions are fast-paced environments where the most significant factor is Murphy’s law. Teams first compete at the regional level, and those who win tournaments get to move on to the state championship. The winners of state championships get to move on to the world championship. I competed in Northern Virginia, one of the strongest regions in one of the country’s strongest states robotics-wise.

Nothing but Net, 2015-16

My relationship with VRC began in my 6th grade year, when I joined with five of my peers to compete in the robotics competition that our school, Stone Hill Middle, was known for at the time. This was my first entry into the world of competitive robotics, and over the course of the year, I completely fell in love with it. I learned the basics of programming in C++ and fundamental engineering concepts such as gear ratios and center of gravity.

Our team in this year got as far as the quarterfinals of regionals competition. But this was more because of a lack of strategy and funding than because of a lack of engineering ability. Our team functioned like a well-oiled machine, and our robot was certainly one of the best in the state. I have many fond memories of working late into the night with my friends before competitions, and one time even building a mechanized catapult so powerful that it shook the whole house when it ran and drained a 9V battery in seconds. Actual competition performance aside, this was and always will be my favorite year of middle school competition.

Starstruck, 2016-17

My second year of competition was more memorable for its vices than for its accomplishments. One of my close friends on the 6th grade team—who’d ended up as our de facto leader—had to move across the country, taking with him his father, a professional engineer who had helped us learn the fundamentals. Others on our team dropped the project, so those of us had to scramble to find new people to fill the gap that had been left behind. The end result was a high-friction team without any real source of guidance or concrete strategy. I can’t actually recall how well we performed, but I know we didn’t get to states.

In the Zone, 2017-18

After the failures with our second year, our team completely dissolved. Some dropped Vex entirely; others transferred to other teams that looked more promising. The creation of a new middle school that many students from Stone Hill got rezoned to didn’t exactly help, either. Because I didn’t have connections with people on existing teams, I had to get randomly assigned by my Technology Education teacher into a new inter-school team that had formed out of current and transferred Stone Hill students.

None of us really knew each other at the beginning, and team roles were completely up in the air. This led to a lot of friction and infighting that got in the way of building and programming a solid robot. We still didn’t have a solid mentor who truly understood engineering and computer science, so we struggled on that front too.

That said, this was the first year where we really started thinking about strategy. We took the time to fully understand the game, and discovered this wonderful component known as the skills competition. The skills competition offered a way to qualify for states without actually winning a regional tournament. Because many highly skilled teams qualify multiple times by winning multiple tournaments, extra slots are given out on the basis of your team’s ranking in the robot skills competition. Skills is far easier to do well in because it doesn’t involve an alliance partner or opponents, and thus there’s a lot less randomness which could affect our runs. Veteran VRC competitors would probably laugh upon hearing that it took me two years to understand this, but this was the unfortunate reality of trying to compete without an experienced mentor onboard who fully understood the game.

With this newfound knowledge, we were able to make it to states despite not winning any regional tournaments. It’d been a dream of mine ever since our failure in 6th grade to reach this point, but because our robot wasn’t really functionally “better” than what we had in previous years, it didn’t feel like a true accomplishment. I ended my last competitive season unsatisfied with the way things had panned out in middle school.

High School — Back with a Vengeance

After the frustration of my 7th and 8th grade years, I resolved to move on from the competitive robotics world in high school. But opportunity came knocking in my sophomore year when a friend of mine, who’d also competed in Vex during middle school, asked me to co-coach a new middle school Vex team of 6th graders. Despite my mixed feelings about the competition, I couldn’t deny that Vex had been the source of my love for STEM and had taught me many principles which had come in handy in high school. I wanted to share this experience with others (and maybe also get a little revenge for my middle school circumstances), so I accepted the offer to be a coach. The small team of middle schoolers I took charge of would soon become one of the strongest teams in the state, regularly competing at the Worlds level.

Tower Takeover, 2019-2020

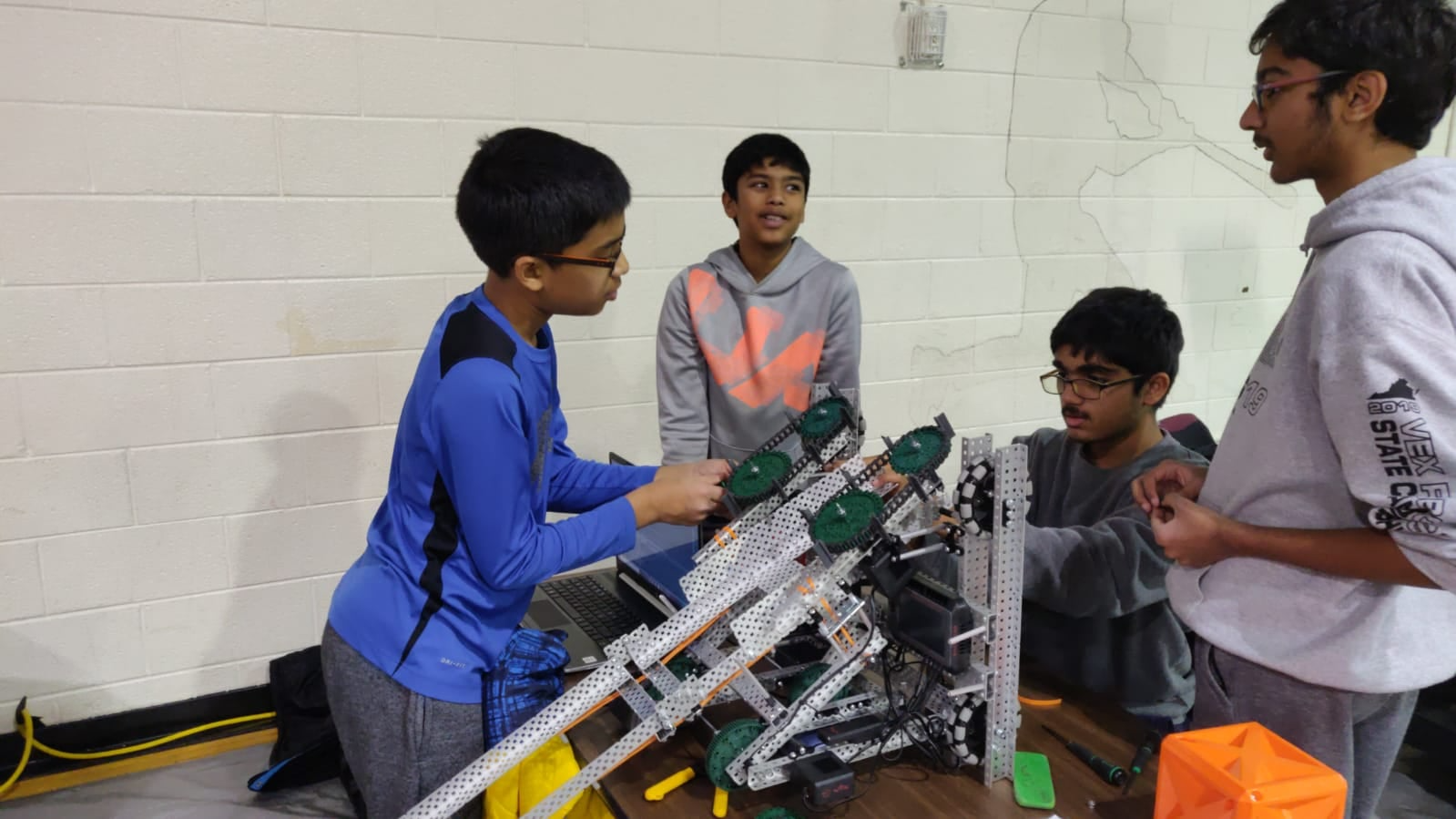

Both coaches working with the team to diagnose a software bug at an early regionals competition.

Both coaches working with the team to diagnose a software bug at an early regionals competition.

We started work as soon as the competition rules were released, in the summer after the students’ 5th grade. I soon found that coaching a team was an entirely different challenge from competing, especially since the team was essentially composed of 5th graders. Not only did my friend and I have to teach them the fundamentals of engineering, but we also had to instill discipline and a strong work ethic. We had to pull them away from their play and show them what the real world of robotics was like.

Of course, it helped that every single one of them was brilliant and had the same love for robotics that my friend and I did. Once we got them to shift their attention towards our robot, we were able to work wonders that never would’ve been possible in my 6th grade year. Having two experienced mentors who understood engineering and knew the game in and out let the students reach their fullest potential. The team won multiple regional competitions, qualifying for the Virginia State Championship. After further robot improvements, they qualified for the VRC World Championship through the state skills competition. Sadly, the worlds competition that year was cancelled due to the pandemic.

The team’s 6th grade robot before states, holding its maximum of 9 cubes.

The team’s 6th grade robot before states, holding its maximum of 9 cubes.

Change Up, 2020-2021

The team ironing out their robot before states.

This year of competition was unique in Vex’s history because of the pandemic. No in-person events were held; competitions were instead decided by skills scores alone, based on recordings from runs done within participants’ homes. This gave our team a unique advantage, because we both lived near enough to each other to meet regularly during the pandemic and we didn’t have to worry about the randomness of tournament brackets.

My involvement was much less this year due to COVID-19 and the pressures of junior year, but the team proved that they didn’t need it, winning the Virginia State Championship and performing incredibly well at the virtual worlds competition.

The team’s autonomous skills run, executed entirely without driver control.

Tipping Point, 2021-2022

Tipping Point is what I consider to be my crowning accomplishment in Vex Robotics. My schedule only freed up enough to start helping out right before the states competition, after all my college applications were over and REVERB was on track to an on-time completion. What I found when I returned was a team that had grown overconfident and complacent because of their easy pandemic victories. My fellow coach and I both agreed to push them extra-hard for states to make sure they could perform as well as we knew they were capable of.

At the States competition, we had to take a few losses early on because of mechanical problems with the robot. But these were diagnosable and repairable; the real damage was to team morale, as the reality set in that we weren’t in a virtual competition anymore. As a coach, even though I wasn’t responsible for actually constructing the robot and fixing problems, I was responsible for making sure the team was functioning at its best. Because of my experience reviving TJ Space Program after the pandemic, I had the skills to turn things around by instilling into our team the same faith and confidence that I had.

So that’s what I did. I rounded everyone up during our lunch break with my co-coach and we gave them the necessary talk about how we were more than good enough to win. Then I started handing out tasks and getting people to work fixing the issues we had. Once lunch was over and we returned to matches, we went on a winning streak that further fueled our high and pushed everyone to work even harder. At several points through the competition, I used my experience with failure in my middle school years to preemptively point out issues such as unreliable hardware, loose wires, and loose joints. We ended up placing first place in qualifier matches and winning the state championship for the second year in a row.

The team and their Technology Education teacher with their robot after winning the VRC Virginia State Championship.

The team and their Technology Education teacher with their robot after winning the VRC Virginia State Championship.

The team with both coaches holding their state championship banner and trophy.

The team with both coaches holding their state championship banner and trophy.

The journey doesn’t stop there, though, because after states was the world championship, and the team wanted to completely redesign their robot to keep up with the competition. In preparation for this, I distributed work, set deadlines, and created a schedule to get everything done over the next two months. Then, in May of 2022, we all flew to Dallas, Texas for the team’s first in-person VRC World Championship.

2022 World Championship, Dallas, TX.

2022 World Championship, Dallas, TX.

The middle school competition took place over two days, and our performance followed a similar pattern to our state competition. We were placed in one of the most difficult divisions, and our tournament bracket was stacked against us. If that weren’t enough, the robot faced various software and mechanical issues that we weren’t able to solve at the competition itself.

So that night, my co-coach and I did the same thing that we did at states: rallied the team, gave them a talk about confidence, and got things moving again. We worked very late into the night, slowly solving issues at their root one by one. The next day, we performed far better, winning incredibly difficult matchups and showing the best teams what we were capable of. We ended up losing in the quarterfinals of our division’s elimination rounds because of unforeseen randomness in alliance selection, but that outcome doesn’t really bother me. I know that our entire team performed at its best, and at the end of the day, that’s what I value in an experience such as this.

Slow motion video of our robot’s game-changing 0.8 second autonomous goal rush, tested at home before the World Championship.

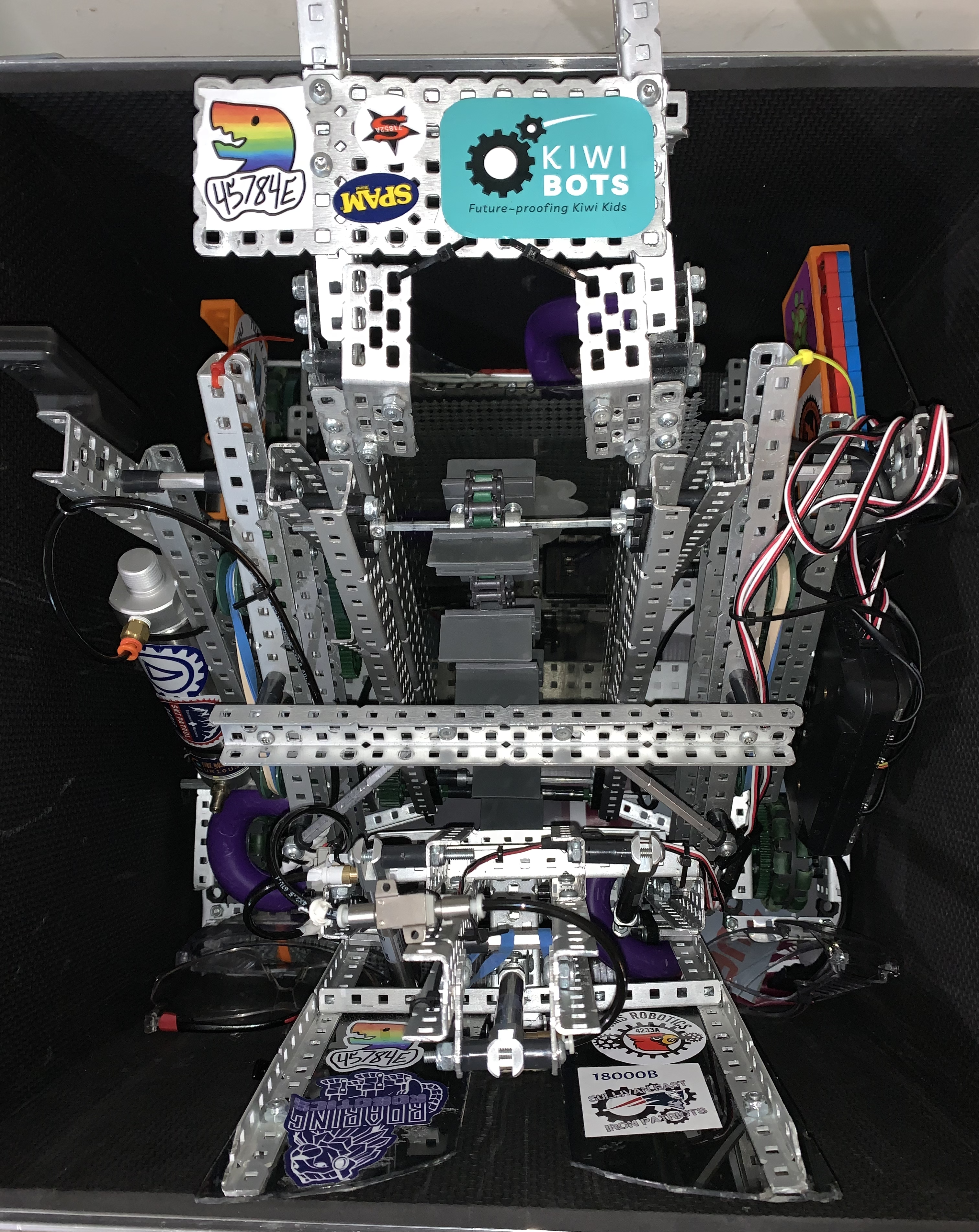

The team’s final robot, by the end of the World Championship.

The team’s final robot, by the end of the World Championship.

What’s Next?

Now that I’ve enrolled in college, I’ve moved on from coaching my team to new opportunities in Austin. My co-coach, however, is with them for at least one more year. The team has graduated middle school and plans to continue competing at the high school level; at the time of writing, they’re in the process of acquiring sponsorships and are designing their robot for the next Spin Up competition.

As of the time of writing, I’m ready to move on from Vex towards real projects and research that produces results more significant than a trophy or banner. But there is no forgetting the role Vex played in my life up to now, as a driving force for my love of STEM.