Opinion — Bots will Win the Detection War

For nearly the internet’s entire history, websites have been at war with automated requests (known as “bot” requests) that attempt to exploit their services. The war has resulted in an arms race of websites trying to develop increasingly effective Turing tests and bots getting increasingly effective at defeating them. From the very first instance of distorted characters being used on AltaVista’s search engine to confound optical character recognition systems and protect the service from bots, to the original CAPTCHA (which stands for Completely Automated Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart)’s distorted text with added markings, to today’s Google reCAPTCHA V3, bot detection technology has advanced and been defeated by competing advances in bot technology.

The very first bot detection test on AltaVista’s website, circa 1997.

These days, the pursuit of progressively better Turing tests has largely been driven by Google’s free reCAPTCHA service: the most recent iteration not only allows most human users through without ever raising an eyebrow, but also presents incredibly tough challenges for automated bots to solve. When human users solve those challenges, the responses help with everything from digitizing books to creating labelled datasets for machine learning models.

There’s just one problem: those “incredibly though challenges” are actually really, really easy for modern AI models. Not only that, but the information required to create a CAPTCHA-solving bot is freely available, and with minimal programming experience, anyone can implement a CAPTCHA solver into a malicious bot. To prove my point, I made my own reCAPTCHA solver.

reCAPTCHA Solver

A low-effort recording of my CAPTCHA solver that I definitely did not make while in class. Bonus points: Asahi Linux running on my Mac.

This bot uses Selenium to control a web browser and interface with the reCAPTCHA element on screen. It first tries to simply get through by clicking the checkbox, and when that fails, it requests an audio challenge, downloads the audio, passes it through a standard Python speech recognition library (other guides even suggested using Google’s own speech recognition API), and puts the answer in the text field. It then hits submit and voila, CAPTCHA solved. The code here to actually solve the CAPTCHA is scarily simple:

request.urlretrieve(page.get_audio_src(), self.utils.path('captcha.mp3')) # Download audio for this challenge

# Convert mp3 to wav to improve quality for speech recognition

pydub.AudioSegment.from_mp3(self.utils.path('captcha.mp3')).export(self.utils.path('captcha.wav'), format='wav')

# Speech recognition

recognizer = Recognizer()

recaptcha_audio = AudioFile('captcha.wav')

with recaptcha_audio as source:

audio = recognizer.record(source)

os.system('rm captcha.wav captcha.mp3') # Delete captcha audio files once no longer necessary

try:

text = recognizer.recognize_google(audio)

except speech_recognition.UnknownValueError: # If speech not recognized

# Code to click button to request new challenge

The hardest part is actually interfacing with the website in the first place and finding the right elements to click. With Selenium’s find_elements() searches and inspect element, this is a tedious problem to solve, but not a difficult one. I was able to put this solver together in less than a day of total work.

What Does This Mean for Bot Detection?

If there’s anything to take away from this, it’s that bot detection will always be a losing battle. Whenever an AI model is designed that can more effectively tell computers and humans apart, a counter-model can be designed with the same basic architecture that’s capable of defeating it. But the counter-model has an advantage: humans themselves are naturally fallible. Turing tests must be able to distinguish people of all backgrounds from bots, and that gives bots a lot of margin for error where they can be imperfect at a task while still looking like a human. Stricter bot protection measures will inevitably result in more false positives for humans and worse experiences for real site visitors.

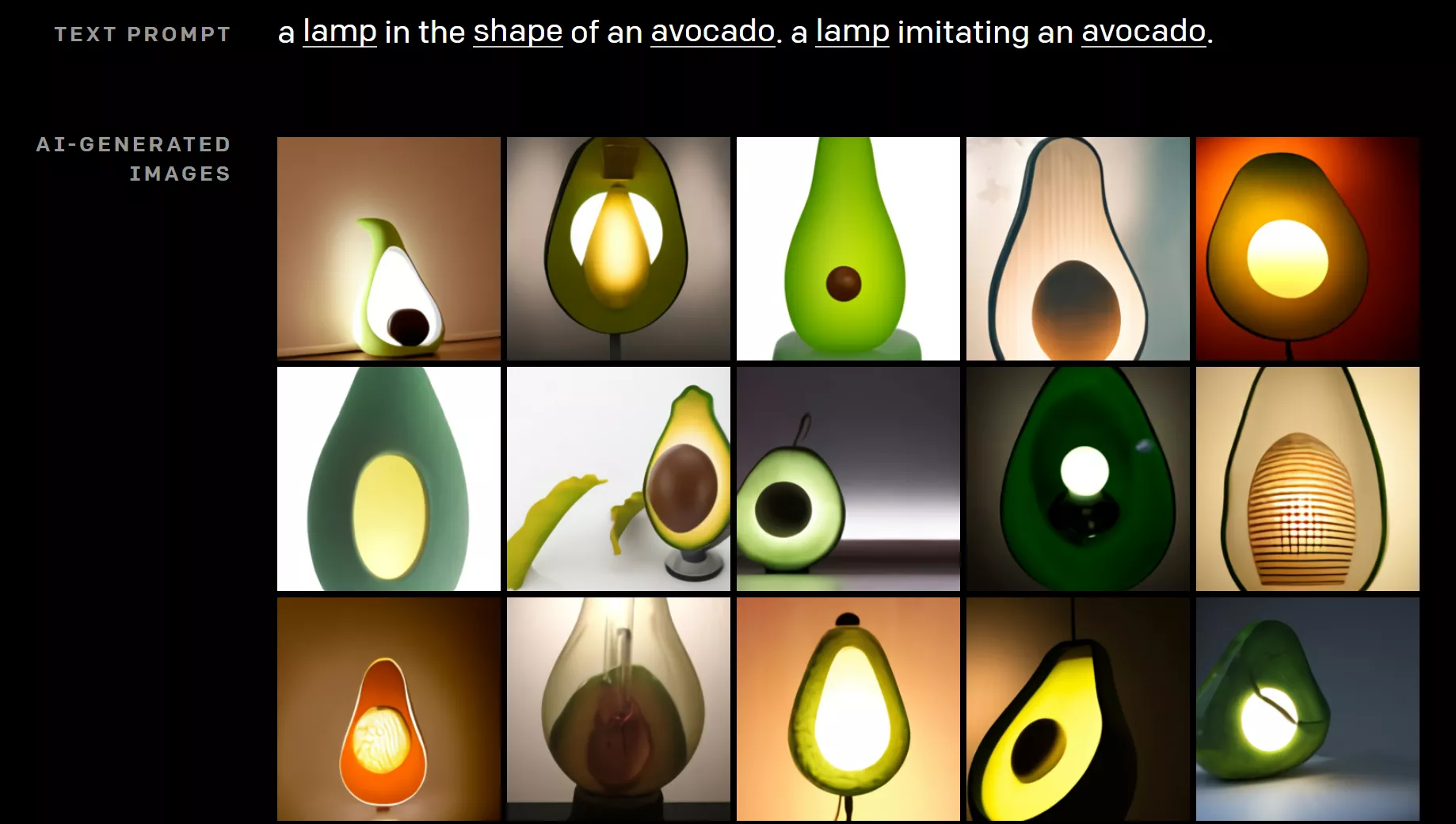

This leaves only a few paths for the war against bots to take moving forward. The first is to simply gatekeep AI technology so that malicious users can’t access it. It’s not possible to develop a counter-model if the technology used to create the Turing test isn’t publicly released. This avoids the kind of problem where Google’s own speech recognition API can be used to defeat its audio reCAPTCHAs. Some companies have already taken this approach, such as OpenAI with DALL-E.

Example images generated by DALL-E.

But the open source community is what has driven innovation in tech at the breathtaking pace that we’ve seen over the past few decades. Once companies start hunkering down with their trade secrets, we can easily end up in a pharma industry-like situation, where patents and information control allow companies to jack up the prices of essential drugs at the expense of ordinary people. Openness and freedom have served as a beacon of collaboration and good faith in the world up until now; potentially losing that because of malicious hackers writing bots is a scary thought. Not to mention that technology never stays locked up for long; information will get out one way or another, and the moment it does, the arms race will be back on.

The other “bad ending” we could have here is features such as two-factor authentication and multi-step identity verification becoming the norm across the internet. Services are already moving in the direction of rigorously vetting their users to ensure that they’re real people, and as the threat from bots increases, that trend will only accelerate. The obvious worry here is what will happen to all that data once identity verification is complete. Without adequate legislation on how companies can handle sensitive user data, it’s very easily possible for all that information to find its way onto an insecure centralized server that becomes the victim of a data breach in the future.

And even if we ignore the security problems, we’re still faced with the reality that deanonymizing internet users is a significant step backwards in terms of digital privacy and freedom. One of the most beautiful things about the internet is that people have the ability to speak their mind without fear of retribution in real life. Restricting anonymity and the freedom of speech are steps that authoritarian regimes in Iran and China are already taking to control the incredible liberties that the internet offers; do the rest of us really want to join them under the pretext of a “bot-free” internet?

Not to mention that verifying someone’s real-world identity won’t work to prevent bots in the long run anyways. Two-factor authentication can be circumvented by attackers buying temporary phone numbers. More invasive methods such as asking for a photo of a valid government ID and a photo of the user will soon be ineffective as well, as the technology required to generate photorealistic images of faces and IDs isn’t too far off. Nothing short of forcing the user to appear in person at a physical site with multiple forms of governmental documentation can work forever, and even that method is vulnerable to changes in physical faking technology (aside from the obvious problem that nobody wants registering for a service to feel like a visit to the DMV).

A Happy Ending?

Both of the above options seem pretty dystopian, but maybe there’s another way out of this situation. Maybe our goal shouldn’t be to fight against bots, but to embrace them as an inevitable part of the internet of the future. Cybercriminals aside, most people making bots to interact with the web don’t actually have malicious intent. They might be open source intelligence gatherers scraping the web with automated queries. They might be ordinary people looking to snipe a product in an online auction without wasting their own time watching the site. They might be people looking to add features and functionality to basic chats by creating a chatbot capable of executing basic commands.

People have an innate assumption that all bots are evil and malicious (perhaps it stems from the Hollywood portrayals of AI takeovers). Now that the Turing test war is in full swing and the outcome is gradually becoming clear, maybe it’s time to revise that assumption. Maybe instead of forcing researchers to fight against Google’s protections on its search engine, we should create better ways for people to conduct large-scale automated queries of the internet, and stop putting sensitive information on public websites for them to discover. Maybe instead of highly competitive online auctions designed for human bidders, we should design auction sites with the assumption that people don’t want to waste time spamming a button, and instead integrate automation into the process of purchasing a product (perhaps a watchlist that automatically makes a purchase when a target item appears for sale below a certain price). Maybe instead of trying to keep all bots off our social media platforms, we should allow users to create non-malicious chatbots that extend the functionality of our chats (Discord has already made great strides in this direction). Maybe instead of having zero-tolerance policies for alternate and fake accounts, companies like Facebook can offer formal support for intelligence research while providing those same tools to individual users in an easy-to-use format so that they can better manage their own digital footprint.

Improving tech literacy is another huge step that would have an infinitely better effect on malicious cyberattacks than creating a better CAPTCHA. It’s an unfortunate reality that people in today’s world simply aren’t equipped to think critically about the things they see online. It sounds almost silly to say “Don’t believe everything you read,” but that very advice would address most of the misinformation and extremism problems caused by bots and trolls on Facebook without any complicated AI at all. It should be common knowledge to check the sources of information and investigate conflicting viewpoints before drawing a conclusion. The fact that bots have been able to wreak such havoc on online political discourse is more a reflection of our society’s inability to think than it is a reflection of poor Turing tests.

This doesn’t just apply to social media and misinformation, either. Phishing emails wouldn’t exist if people weren’t falling for them. Thirst trap bots on Instagram wouldn’t exist if people weren’t clicking. Deepfakes wouldn’t exist if people didn’t have a tendency to believe everything they see without questioning. The only way to really solve this problem is to improve tech literacy and teach people how to use the internet safely.

This is a reform that needs to start at the school system. I’m sure everyone who was in school during or after the time the internet started to explode in popularity has many fond memories of watching comical “internet safety” videos that were so disconnected from reality that they offered no value to students other than as a joke. That kind of nonsense is how we created a generation that’s having to learn the hard way what the rules of the internet are, and that doesn’t seem to care much about digital privacy or security. There needs to be serious effort put in to teach our children how to use the internet safely and productively, and that effort needs to be led by real cybersecurity experts who can provide up-to-date information on the most recent threats faced by internet users.

One of my favorite “internet safety” videos from way back. Definitely very good at terrifying children, also very good at amusing older children, but not good at all at addressing the real, subtler threats that people fall victim to every day.

In the same vein, we need to ensure that people are kept up to date with the latest cybersecurity developments; this is a burden that falls on the hands of Facebook, Google, and other big tech companies who already have a huge amount of people’s attention. Why isn’t Facebook showing message bubbles about how to spot bots and misinformation whenever people open the app? Why isn’t Google showing the latest threats to be aware of on its main page? It’s not fair to expect the everyday person to spend their free time researching cybersecurity; Big Tech has a responsibility to protect its users.

Obviously there are still going to be many cases where telling humans and bots apart is essential—you don’t want bots creating bank accounts or filing tax returns, for instance. The Turing test war is going to continue at least for the immediate future, and our stopgap solution of CAPTCHAs will continue to protect our sites as best they can. But as a society, we need to start preparing for a world where bots are just a part of normal life. That means reinforcing our cybersecurity infrastructure, yes, but it also means making our people more resistant to attacks through education, and it means changing our web services to accept bots and automation as the future.