Opinion — Can Less Democracy Save Democracy?

Yep, I’ve finally lost it and decided to dip my toe into the radioactive cesspool of American politics. This is a terrible idea. Let’s do it.

In recent years, there’s been a lot of… Talk™ of threats to American democracy (not even going to try citing a source on that…). Most of the arguments made on this subject are highly partisan, but let’s step away for a moment from the day-to-day electoral humdrum of culture war mudslinging, AI-enabled hatred, and political violence. Is there a signal underneath all this noise? Is our democratic process really under threat?

I believe there is at least one existential risk to the great American project which hasn’t received enough (serious) attention from either party: the Prisoner’s Dilemma of the national debt.

What is the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

For those needing a refresher, the Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) is a fundamental thought experiment in game theory imagining two suspects of a crime being interrogated independently by the police. The police have only enough evidence to convict both suspects of minor drug offenses, and are thus seeking out a confession to burglary. The interrogators employ a tried-and-true tactic: offer each suspect the chance to confess with the promise that they will go home scot-free if they turn on their partner, condemning them instead to the maximum sentence. If both confess, they will receive some leniency from the judge, but the collective outcome will certainly be worse than if they had kept their mouths shut.

The scenario can be modeled like so:

| Suspect B Stays Loyal | Suspect B Confesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Suspect A Stays Loyal | A: 2 years, B: 2 years | A: 10 years, B: 0 years |

| Suspect A Confesses | A: 0 years, B: 10 years | A: 8 years, B: 8 years |

The key problem identified by game theory is that, if Suspect A expects Suspect B to stay loyal, they ought to defect to minimize their jail time (after all, walking home that evening is a far better outcome than 2 years in jail). Of course, Suspect B knows this, and would much prefer the 8 years in jail that comes with defecting to the 10 that comes from misplaced loyalty. We have thus arrived at a Nash equilibrium, a set of strategies played by all players in a game such that no player could achieve any benefit by changing their strategy. The strategy for both suspects is to confess, and if either tries to choose loyalty, they are guaranteed to suffer a personally worse outcome. The only winners here are the police, who have achieved 16 prisoner-hours instead of 4 or 10.

How can we apply this?

You can probably already see where I’m going with this. Let’s imagine that instead of suspects of a crime, we have two political parties: the Let’s Destroy the Economy While Pretending we’re Saving It Party (LDEWPSIP, say “L-dupe-sip”), and the Let’s just Openly Destroy the Economy Party (LODE party), with some set of mutually exclusive priorities that each party would prefer to spend tax dollars on. LODE is currently in power and expects LDEWPSIP to take back power sometime in the future. LODE must now decide what kind of budget to pass: a balanced budget maximally focused on their priorities, or a deficit budget maximally focused on their priorities. When LDEWPSIP takes back power, they will also have a similar choice to make.

To model this as a PD, let’s switch from explicit cardinal payoffs (like years in jail) to abstract ordinal utility scores, where a higher number indicates a more preferred outcome for that party. You’ll notice that the original PD also reduces to this if you replace cardinal years in prison with ordinal utility scores.

| LDEWPSIP Passes Balanced Budget | LDEWPSIP Runs Deficit Budget | |

|---|---|---|

| LODE Passes Balanced Budget | LODE: 3, LDEWPSIP: 3 | LODE: 1, LDEWPSIP: 4 |

| LODE Runs Deficit Budget | LODE: 4, LDEWPSIP: 1 | LODE: 2, LDEWPSIP: 2 |

The core logic here is that both parties would always prefer more money to go to their priorities over those of the opposing party. Both are rewarded for raising the deficit during their term in power, even though this behavior will lead to unsustainable debt servicing costs in the long term, so both will always choose to do so. Even if the country eventually runs out of fiscal headroom because of this, each party will still prefer to have spent more of that headroom on their policy priorities. Thus, we have a real-life PD.

That’s pretty hand-wavy…

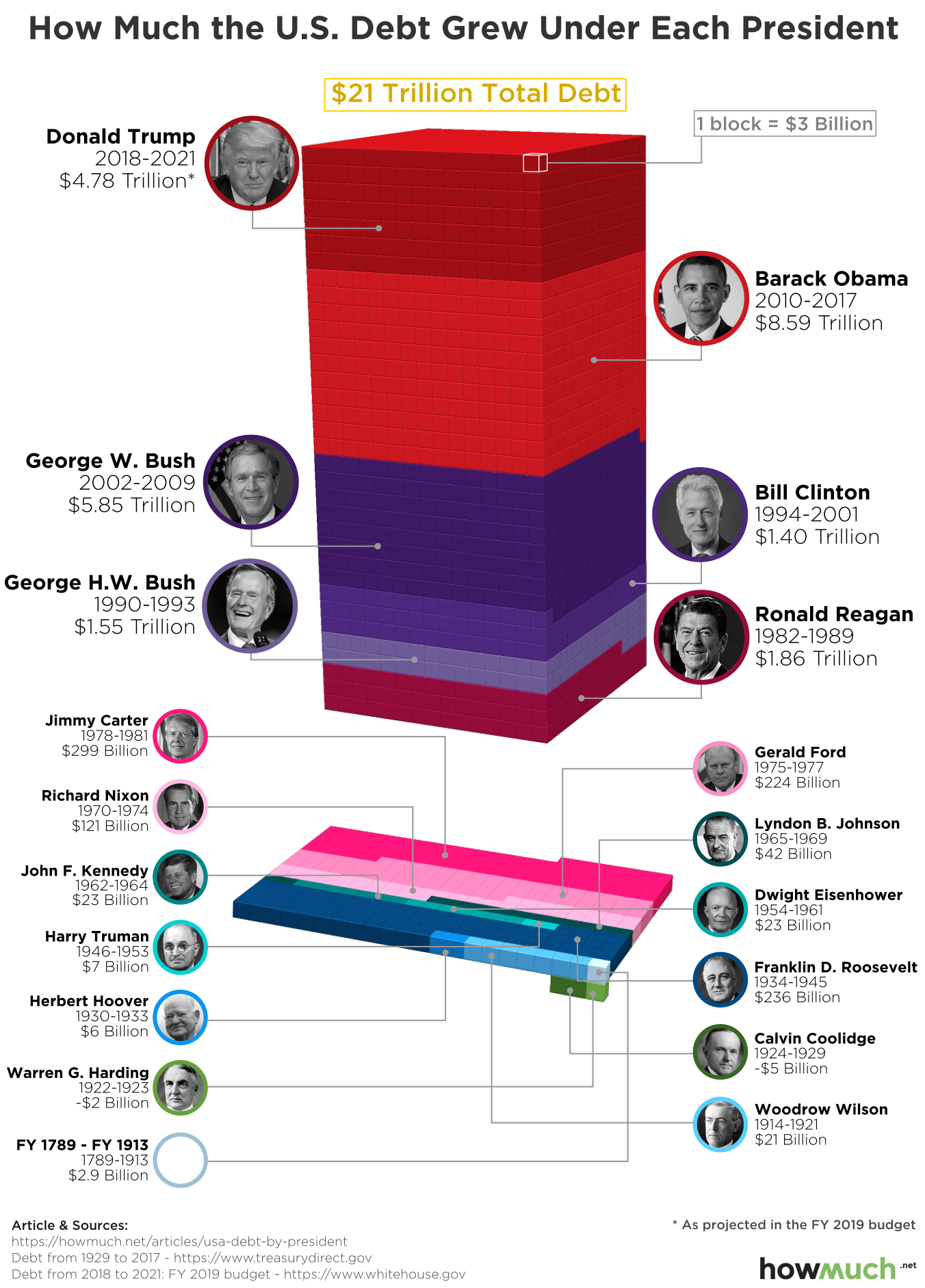

Yes, but it’s supported by the data. We can see the process of our political parties finding the Nash equilibrium in real time by looking at the amount added to the national debt under each recent president:

Extreme partisan deficit spending began with Reagan in the 80s. Clinton actually succeeded in running a balanced budget in the year 2000, but this had exactly the effect predicted by the PD model: giving the opposing party (Bush) even more fiscal headroom to pursue a war in Iraq and Afghanistan, among other spending priorities favored by his political base. Since then, both parties have learned their lesson and become locked into the PD’s Nash equilibrium. The data in this chart ends in 2021; Trump would go on to add $7.4T in his first term, and Biden would add $6.0T. At the time of writing, our national debt stands at $37.8T, and the second Trump presidency is looking to be even more fiscally irresponsible than the first.

So what?

We have to understand that this selfish political reasoning has real consequences. There are only three plausible ways for this game to end.

Option 1: Austerity measures finally bring back some relationship between tax revenue and government spending. A small enough budget deficit could realistically be paid off if it efficiently stimulates economic growth. Despite short-term pain from higher taxes or the loss of popular programs, this would be a better outcome than the others. But from the reaction on Capitol Hill to cuts to even a non-essential program like public broadcasting and a persistent inability to tax the rich, it’s also the least likely to actually happen.

Option 2: Deficits keep growing until the government defaults on its debt. This is hands-down the worst outcome, as it will destroy the confidence domestic and foreign investors have in the American economy. If American bonds, considered everywhere to be the “safest” investment, prove to be prone to failure because of political instability, the subsequent de-risking and panic-selling would cause one of the worst recessions in history. It would be a global catastrophe marking the end of American hegemony and the dollar as a global reserve currency.

Option 3: The Treasury finances the debt with quantitative easing (read “digital money printing”). This is the most likely outcome, as it has already been done once during the COVID-19 pandemic to pay for the American rescue plan. This spending was immediately followed by extreme inflation that was a major factor in earning Trump his second term in the White House. A similar method could theoretically be used to pay down the national debt (after all, the debt disappears if you just create $37.8T and give it to all the bondholders), but would likely cause inflation an order of magnitude worse than what was seen during COVID. The rich will survive because of inflation of their stock portfolio, but this would be devastating to anyone who lives paycheck to paycheck or keeps their savings in dollars.

In other words, we are staring down the barrel of an existential threat to our democratic system and way of life. No matter which of these possibilities ultimately occurs, people will be exceptionally angry when they’re forced to pay a bill that they’ve been promised time and again will never come due. We can already see similar chaos in France resulting from even a proposal from their Prime Minister that unsustainable borrowing can’t continue forever. Just imagine how angry average people will be when they find out their pensions are being cut, or they got laid off in a recession, or bread and eggs cost twice what they used to.

Can we prevent this?

I am not even remotely qualified to suggest a solution to this problem. So I went ahead and wrote a paper on a potential solution:

In short, we may be able to break the PD gridlock by adding a third player: the actual holders of the bonds and owners of public debt. These people are purely rational economic actors and entirely disconnected from electoral politics, seeking only to maximize their own profits by investing in American stability and confidence. A debt default would be catastrophic to their investment as their loan would never get paid back. Quantitative easing would be similarly catastrpohic, as despite their principal having been returned with interest, that money is now worth far less than it used to be.

The bond market already provides an implicit check on partisan spending by being able to define the interest rate at which the risk of a default is considered worth it. Rising bond interest rates during Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs is widely considered to be a reason why that policy was ultimately walked back to a less damaging version. Trump and Capitol Hill were forced to pay attention, as raising the borrowing costs could have exploded the cost of their upcoming spending package, the Big Beautiful Bill.

But I worry that even this check will ultimately fail for the same reason that Clinton attempting to balance the budget backfired. Making borrowing costs higher reduces the cardinal payoff of extreme partisan deficits, but the core PD logic still applies: if the maximum debt level tolerable by investors is ultimately going to be hit anyway, isn’t it better for more of that spending to go to LODE’s priorities instead of LDEWPSIP’s? The ordinal utility socres are still the same, and the game still reduces to a PD. Trump walking back Liberation Day because of the bond market getting “yippy” may have been a second Bill Clinton moment, and a future Democratic administration may completely ignore that signal and push further towards the Nash equilibrium.

This is the motivation for my proposal: giving bondholders real power over the political process in a new Bondholder’s House. This is inspired directly by Proof-of-Stake block validation and governance systems on blockchains, specifically the Ethereum cryptocurrency. The logic is that individuals holding the greatest number of coins have the most “stake” in the integrity and success of that currency, and thus are incentivized to act honestly in block validation decisions to protect their investment.

I would recommend reading the full paper for a detailed explanation of how this could work, but the basic idea is that if bondholders had some limited ability to veto budget proposals that negatively impacted their investment, we might yet be able to avoid a debt crisis. Taking away power from democratically elected leaders and placing it in the hands of self-interested, profit-motivated individuals may be exactly what we need to escape the PD we’re currently locked in.

To demonstrate, we can change our PD model to include the party currently in power as one player, and the Bondholder’s House as a second player:

| Bondholder’s House Approves | Bondholder’s House Vetoes | |

|---|---|---|

| Party Passes Balanced Budget | Party: 2, Bondholders: 2 | Party: 1, Bondholders: 1 |

| Party Runs Deficit Budget | Party: 3, Bondholders: 1 | Party: 1, Bondholders: 2 |

With this modification, running an extreme deficit is no longer a strictly superior strategy to passing a balanced budget. In fact, because the Bondholder’s House makes its decision with full information of what decision the party in power has made (the game is sequential rather than simultaneous like the original PD), the party can expect the bondholders to act with economic rationality: approving the budget if it’s balanced, and vetoing it if it’s fiscally irresponsible. We can thus simplify the game by removing the Bondholder entirely (because their behavior is known without ambiguity):

| Party Decision | Expected Party Payoff |

|---|---|

| Pass Balanced Budget | 2 |

| Run Deficit Budget | 1 |

And now we have successfully reframed the PD as an agreement game, where it’s mutually beneficial for the party in power to spend responsibly, and for the bondholders to respect the democratic process and approve that spending (similar to how the House of Lords in the UK restrains itself to protect its legitimacy unless absolutely necessary; if it overstepped, the people would demand to be rid of it).

Is this ever going to happen?

No.

But perhaps it’s still useful to understand why we’re in our current position with the national debt and what kind of solutions need to be explored to do something about it. Adding a check on the legislative branch’s power to pass budgets (which would have to be a constitutional amendment to give this Bondholder’s House any real power) would reframe the PD, but it would also deliberately hand power to a cabal of rich elites. Even suggesting such a plan would be political suicide.

What this thought experiment does do is point us in the right direction. If we’re going to solve our debt problem, we need to figure out how to reframe the PD that our politicians are locked in. I will leave it to someone with actual qualifications to figure out a less invasive way to achieve that.

Personally? I’m an optimist to a fault, and despite all the evidence I’ve laid out pointing to the fact that this problem won’t be solved until it’s too late, I still believe that somebody somewhere will do something about it. Just… maybe after this current wave of reality television politics.